Denial and Denigration: How Racism Feeds Statelessness

The chapters

Minorities and indigenous peoples are especially vulnerable to statelessness. Through research, films, photos and case studies, this website explores how statelessness is often an outcome of discrimination and racism.

- 01

Introduction

Numbering many millions, the world’s stateless population spans a vast range of ethnicities, religions, languages and socioeconomic conditions. Their lack of formal citizenship of any country can leave them excluded from state structures,…

3 min read

- 02

Statelessness & minorities globally

Stateless people are found all over the world, in every region and every state. However, Asia and Africa are the two continents that host the largest number of stateless people. This is due to the widespread combination of weak systems of…

6 min read

- 03

Film: statelessness and minority rights

A short film introducing statelessness and how it affects minorities and indigenous communities around the world. Photo: Murle young women in South Sudan. Credit:…

1 min read

- 04

Causes of minority statelessness

The causes of statelessness around the world are remarkably consistent: transfers of sovereignty or contested territory, discriminatory or defective laws, suspicion of communities divided by international borders or who are perceived as…

9 min read

- 05

Asia

Asia hosts the largest number of people identified by UNHCR as being stateless, including the largest single population of stateless persons in the world, the Rohingya minority of Myanmar, numbering almost one million. However, statelessness is…

7 min read

- 06

From discrimination to ethnic cleansing – the fate of Myanmar’s stateless Rohingya

by Nicole Girard Rohingya are an ethnic, religious and linguistic minority, traditionally concentrated in the northern part of Myanmar’s western Rakhine state, on the border with Bangladesh. Most practice Sunni Islam and speak the Rohingya…

0 min read

- 07

Caught between the sea and the land: the dilemma of stateless indigenous seafarers

by Nicole Girard International media attention on indigenous sea nomadic populations increased dramatically after the Indian Ocean tsunami that struck the coast of Thailand in 2004. Most examined traditional knowledge of the ‘sea gypsies’…

0 min read

- 08

Indigenous seafarers: photo story

Sama Dilaut, also known as Bajau Laut, are an ethnic group of Malay origin who traditionally live a nomadic lifestyle at sea. They are known to be affected by statelessness (read more in the previous chapter). In the last few decades many…

3 min read

- 09

Americas

The countries of North, Central, and South America for the most part share a common tradition of attribution of citizenship based on birth in the territory, known as the jus soli rule. Notwithstanding some caveats, this rule broadly provides…

4 min read

- 10

Our Lives in Transit – documentary on ‘legal ghosts’ in Dominican Republic

‘Our Lives in Transit’ is a 30-minute documentary showing life in the Dominican Republic in the aftermath of a controversial law that leaves over 200,000 people doubting their own identity. Rosa Iris is a young and determined…

0 min read

- 11

Europe

Europe has both the most information about stateless populations and the most developed set of standards relating to nationality and discrimination. Nonetheless, statelessness is still prevalent across the region. As of the end of 2016, UNHCR…

3 min read

- 12

The vulnerability of Roma minorities to statelessness in Europe

by Julija Sardelić Europe’s Roma minorities, long victims of discrimination and persecution, are typically the most vulnerable group to statelessness in the region. While there are multiple reasons for this, including state succession and…

0 min read

- 13

Middle East and North Africa

Discussion of statelessness in the Middle East and North Africa is dominated by the special case of the Palestinians, both those living under the Palestinian Authority and those who are refugees in other countries of the region. However,…

7 min read

- 14

Sub-Saharan Africa

The communities within Africa most at risk of statelessness are similar to those in other continents: the descendants of people who migrated to the country before independence; ethnic groups whose pre-colonial boundaries cross modern borders,…

7 min read

- 15

Ways forward and recommendations

The objective of ensuring the right to nationality for all is a challenge that combines technical, political and social considerations, from legal and administrative reform of citizenship policies to a broader expansion of a country’s…

7 min read

-

Numbering many millions, the world’s stateless population spans a vast range of ethnicities, religions, languages and socioeconomic conditions. Their lack of formal citizenship of any country can leave them excluded from state structures, without the right to vote or access basic services such as healthcare or education. In extreme cases, statelessness may leave them vulnerable to violence and mass displacement.

There are many factors that can contribute to the prevalence of statelessness, from poor registration systems and patrilineal citizenship laws to contested national borders and forced migration. However, beyond the particular administrative and legal mechanisms that create and maintain statelessness, there is frequently a more fundamental force at play – discrimination. Indeed, for members of certain communities, statelessness is the extension of a long history of exclusion and denial.

While statelessness can affect anyone regardless of their background, including members of dominant or majority groups, the primary focus of this publication is the situation of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities across the world – communities MRG has been working directly with for more than 40 years – who are also stateless or at risk of statelessness. As members of disadvantaged and marginalized communities, often relegated by their governments to the sidelines on the basis of their identity, they make up a disproportionate number of the global stateless population. This is in part because the various factors that can elevate an individual’s risk of statelessness, such as poverty, limited access to judicial systems and a lack of official documentation, often affect these communities in particular.

At the same time, governments may deliberately manipulate nationality law as a tool of repression against particular communities. At its worst, statelessness, far from being an official oversight or shortfall, may be orchestrated to disenfranchise members of a particular ethnicity, faith or linguistic group. The persecution of Myanmar’s Rohingya, for example, has been built on a steady attrition of their civic rights over decades of military rule, and the arbitrary killings, torture and mass displacement inflicted on them has been enabled in no small part by their representation as ‘outsiders’ in their own country.

Recognizing that statelessness is often not an accident but a logical outcome of discrimination, be it direct or indirect, is an essential step to ending the injustice of living without a country. This publication, Denial and Denigration: How Racism Feeds Statelessness, therefore highlights the intersection between minorities and statelessness, demonstrating that the lens of minority rights can provide a valuable perspective to understand why statelessness is still occurring, the ways it is affecting different groups and the steps that can be taken to resolve it.

Who are minorities?

Minorities of concern to MRG are disadvantaged ethnic, national, religious, linguistic or cultural groups who are smaller in number than the rest of the population and who may wish to maintain and develop their identity. MRG also works with indigenous peoples. Other groups who may suffer discrimination are of concern to MRG, which condemns discrimination on any ground. However, the specific mission of MRG is to secure the rights of minorities and indigenous peoples around the world and to improve cooperation between communities.

Photo: Refugees, thought to be Syrian Kurds, at Idomeni camp in Greece. Credit: Julian Buijzen.

-

Stateless people are found all over the world, in every region and every state. However, Asia and Africa are the two continents that host the largest number of stateless people. This is due to the widespread combination of weak systems of documentation, including low rates of birth registration, and laws and practices that discriminate in various ways or provide access to nationality only on the basis of descent: that is, only to a person who has at least one parent who is or was a national of the country. Where no rights at all to nationality are granted based on birth in a country, even over multiple generations, many are left at risk of statelessness.

Statelessness is ultimately an individual status: it is usually the case that not all members of a minority at risk of statelessness are in fact stateless, since slightly different accidents of birth or life history may mean that some will have been able to obtain recognition of their nationality. Equally, gaps in the legal framework can leave individuals at risk of statelessness within majority groups, especially children born of foreign fathers, or whose parents are unknown or who are separated from their parents. Other intersecting vulnerabilities, such as poverty, can also exacerbate the risk of statelessness.

Nevertheless, it is the case that minorities make up a large portion of the world’s stateless population, and in many cases face distinct barriers to securing recognition within their country. This is due in part to indirect discrimination: as marginalized communities, they are especially likely to struggle with lack of resources and limited access to official systems of registration – both issues that typically raise the risk of statelessness. However, the factors may also be much more direct. While statelessness may result from oversights or failings in a country’s legal and administrative systems, the persistence of stateless populations is often the direct result of discriminatory state policies. Sometimes these may be written into the law, but more often they are based on formal or informal practices that affect particular groups disproportionately. Communities that have been resident over many generations within the borders of a state may be presented in official discourse as ‘foreigners’ or ‘migrants’, to justify their exclusion from social and political integration.

One reason why members of certain minority groups are particularly vulnerable to statelessness is because national politics is closely intertwined with ethnicity, religion or language. In this context, unscrupulous leaders may use nationality law as a means to exclude communities from participation in the political arena. In Zimbabwe, for example, descendants of farmworkers brought to the country from neighbouring territories during the colonial period of British rule were for many years recognized as Zimbabwean. When an opposition party gained strength that they supported, large numbers were prevented from voting on the basis that they held nationality elsewhere and were therefore not Zimbabwean – but many were left stateless. In Côte d’Ivoire, descendants of labourers imported by the French also came to be denied recognition as nationals, since to do so would upset the balance of electoral power. Therefore one of the most direct outcomes of statelessness is also often one of its main drivers – the exclusion of particular groups from voting.

Many of the most significant stateless populations, such as Myanmar’s Rohingya – who, numbering more than a million people, make up the single largest stateless population worldwide – have been left without citizenship as a direct result of discriminatory policies targeted against them. Groups that are particularly vulnerable to statelessness include:

- ethnic, religious or linguistic communities divided by international borders.

- descendants of historical migrants, especially those who moved or were moved to a territory before it gained independence.

- nomadic populations, whose traditional routes cross international borders.

- minority communities that generally face discrimination in that society.

Statelessness impacts in numerous, complex ways on individuals and communities who find themselves excluded from the rights and benefits of citizenship. At one extreme, in 2017 Myanmar dramatically escalated the use of violence against its Rohingya minority, resulting in massive displacement across the border with Bangladesh, in a campaign that a team of UN observers believed could amount to crimes against humanity. At the other end of the spectrum are the Russian-speaking populations of the Baltic states, especially in Estonia and Latvia, a legacy of the Soviet era. Though not recognized as citizens, they are legal residents and enjoy most of the rights of citizens, except the right to vote and stand for public office. In all contexts statelessness has significant negative impacts on a person’s ability to function as a full member of society.

Stateless people, like minorities in general, are amongst the most marginalized in any society. Besides being vulnerable to exploitation for dirty and dangerous work due to their lack of legal citizenship, they cannot organize to defend their rights because they are at risk of detention and deportation. At the same time, without a documented nationality, they may face severe difficulties in travelling and even struggle to seek asylum without legal documents – a situation that can leave them in a limbo while the state authorities seek to identify a country that is willing to recognize them as its own. Ironically, one of the reasons for rejection of refugee status may be that a person cannot prove their country of origin. Even outside the context of conflict or violence, lack of nationality documentation can leave both adults and children vulnerable to trafficking, as in the case of stateless minorities in Thailand.

Perhaps most importantly for day to day life, statelessness may mean that a person is denied a job, the opportunity to go to school, access to health care, even the right to an officially recognized marriage or to register the birth of children. In the Dominican Republic, despite the Constitution recognizing the right to education, Dominico-Haitian children may struggle to access schooling if they cannot provide documentation. As a result, they may find themselves excluded from the public education system. But there are also many capabilities associated with proof of nationality or identity – such as opening a bank account or buying a SIM card or mobile phone – that are not formally human rights, but without which it may be impossible to participate in contemporary society on equal terms.

While the impacts vary in form and intensity, from denial of voting rights and limited education opportunities to detention and targeted attacks, the effects are especially acute for minorities who may already struggle to secure their needs. In many cases, the assertion that members of a particular minority are not nationals provides an official pretext for states to ignore or persecute communities who, for political or social reasons, are regarded with suspicion by governments and the dominant ethnic, linguistic or religious groups. Stateless Roma in Europe, for example, face even greater obstacles in accessing their rights than other Roma, who are already often a denigrated minority.

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that ‘Everyone has a right to a nationality’ and that ‘No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality’. Most of the main human rights treaties adopted since that date include provisions aimed at ensuring respect for the right to a nationality, including in particular the almost universally ratified Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990). In addition, there are two international conventions that provide more specific guidance on the systems needed to protect stateless persons and end statelessness: the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness.

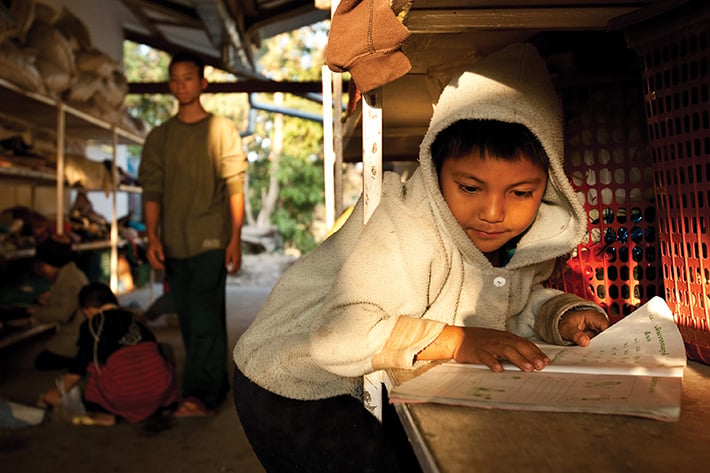

Photo: A child from the Akha hill tribe in Thailand. Credit: RIBI Image Library.

-

A short film introducing statelessness and how it affects minorities and indigenous communities around the world.

Photo: Murle young women in South Sudan. Credit: UNMISS.

-

The causes of statelessness around the world are remarkably consistent: transfers of sovereignty or contested territory, discriminatory or defective laws, suspicion of communities divided by international borders or who are perceived as different or threatening, lack of legal and administrative protection for children at risk of statelessness, and the risks created by migration (especially forced or undocumented migration). All of these are issues that, where a culture of discrimination already exists, can impact especially on minorities, even if they have been present in the country for multiple generations – or longer than those discriminating against them.

State succession

The most common moment for the creation of substantial populations of stateless persons is when legal sovereignty over a territory is transferred: during the transition from colonial rule to independence, at the breakup of empires or federal states into their constituent parts, when a region splits off to become independent or on the transfer of territory between one state and another. Those whose ancestors migrated from another part of what was formerly a single territory, or who belong to a community found in two or more of the new states, may find that they are not registered or recognized as nationals of any of them.

Many members of minority groups were left without a recognized nationality following the end of the European empires in Africa and Asia over the three decades after 1945. Among these groups were, for example, descendants of labourers hired to work on tea plantations in Sri Lanka and India; farm workers imported, often forcibly, to Congo by the Belgians or to Côte d’Ivoire by the French; or Asian and Middle Eastern labourers or traders who followed opportunities in Africa or elsewhere in Asia during the colonial era.

Others, while not migrants, were nonetheless never recognized as forming part of the body of citizens when a newly independent state was established – again, a situation that particularly afflicted certain minorities. Among these are the members of the Kurdish minority whose ancestors were never registered as Syrian in the 1920s, when Syria was created as a territory (initially under French mandate) following the break-up of the Ottoman Empire. Kurdish people from Syria are thus particularly vulnerable among the refugees from the civil war in Syria that broke out in 2011, not least because they may not be able to prove that they are Syrian and thus entitled to refugee status.

More recent cases of state succession have also created populations at risk of statelessness. The transfers of legal sovereignty that arose from the disintegration of the Soviet Union, followed by the civil war in Yugoslavia and the partition of Czechoslovakia, created multiple opportunities for people caught between different rules and facing various kinds of discrimination to find themselves stateless. Among these groups are members of linguistic minorities who found themselves outside their ‘state of origin’ at the date of transfer of territory, including Russian speakers in the Baltic states and elsewhere, or cross-border communities in the Central Asian states, as well as members of communities welcomed by none of the successor states, such as Roma.

Political rifts and conflicts leading to the establishment of new states have also created stateless minorities in their wake. For example, when South Sudan split from Sudan to form a new state in 2011, hundreds of thousands of people of South Sudanese origin living in Sudan lost Sudanese nationality under a legal amendment that denationalized those who the Sudanese government interpreted were entitled to. Among them were many who had been resident all their lives in Sudan, identifying as Sudanese, speaking only Arabic and with no meaningful connection to South Sudan.

Nationality laws that are discriminatory or only based on descent

If the laws of a country provide reasonably open access to nationality, based on birth and residence in the territory, even a substantial stateless population will reduce over time. In this context, successive generations born in the territory acquire nationality either automatically or through naturalization. However, where nationality laws are discriminatory in their content or application, or attribute nationality to children based only on descent, the descendants of those who themselves were not recognized as nationals of the state can remain stateless over many generations. Many minority communities affected by statelessness have been impacted in this way by such discriminatory practices.

Discrimination on grounds of race, ethnicity and religion in nationality law also increases the risk of creating stateless populations, especially among minority communities perceived not to originate from that country. Among those states with the most explicit forms of discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity in their laws are Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Myanmar, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Uganda. Discrimination on the basis of religion and linguistic heritage is common among Middle Eastern and North African countries. Even where there is no discrimination in the law, it may be ubiquitous in practice: for example, in the form of additional administrative burdens for proof of entitlement to nationality applied to people who are members of communities perceived to be undesirable – a situation that frequently afflicts minorities. In the most acute cases, discrimination on these grounds has created large populations of stateless people. Gender discrimination in citizenship law is also a very significant source of statelessness that, while impacting on minorities and other communities alike, can further intersect with other areas of discrimination such as ethnicity.

Border populations and contested territories

Members of nomadic populations, whose traditional territory crosses two or more contemporary international borders, frequently face similar issues. Settled communities are often suspicious of those who have ‘no fixed abode’, and discrimination has impacted their access to nationality rights as well as other services. These groups would include pastoralists in Africa, such as Tuareg (of the Sahel and Sahara desert), Fulani, known as Peuhl in French (found across West and Central Africa), Tebu (found in both Libya and Chad) and Maasai (divided by the Kenya-Tanzania border). Others live in border regions, some nomadic and some not, such as some indigenous peoples in central and southern America or the ‘hill tribes’ of Thailand. The Bajau Laut, or ‘sea gypsies’, of Southeast Asia are another minority literally at the margins of several states and often recognized as nationals of none. While some among these communities may not wish for forced incorporation into the modern state, prejudice among the dominant communities against people of their heritage often means that those who wish to access rights as nationals are unable to do so.

Forced migrants, and their descendants

Those who are forced to flee their homes by conflict or disaster are often at risk of statelessness, since documents may be left behind or lost, destroyed or confiscated during the search for a sanctuary. Without evidence of their connection, these people may never be able to re-establish recognition of the nationality that undoubtedly they are entitled in law to hold.

Disasters and conflict affect majority and minority populations alike, but members of minority groups facing discrimination may be particularly vulnerable (not least because they lack the resources to escape), and are disproportionately affected when the time comes to restore their identity documents. If officials discriminate against minorities they are less likely to accept partial evidence, witness testimonies or assertions of connection to a state from disfavoured minorities than they are from those whose membership is seen as unproblematic.

Among those most at risk of statelessness are children of displaced parents, especially refugees: if these children have grown up in another country that gives them no rights on the basis of birth and residence there, then they may face real difficulties in establishing nationality in any country, even if they have been based there for their entire life. Refugees settled in a host community for many decades or generations may effectively become an established minority in the country, yet still have no or problematic access to nationality provided to them through naturalization or based on birth in the country. Examples would include the stateless Biharis in Bangladesh (some of whom are still waiting for documents despite a positive 2008 Supreme Court decision that ruled that this Urdu-speaking minority were indeed Bangladeshi nationals) and stateless Tibetans in India. European countries with nationality laws founded on descent also need to respond to the need for protection of the children of refugees from statelessness, especially among members of the stateless Syrian Kurdish minority. Even if they are able to return to Syria, gender discrimination means that the children of Syrian women cannot acquire their mother’s nationality if the father is stateless or missing.

Intersectional issues: gender discrimination and child protection

Nationality laws that discriminate on the basis of gender, restricting the rights of women to transmit their nationality to their children, may particularly affect members of minority groups. Gender discrimination is the most common form of explicit discrimination in nationality laws: although the trend is increasingly for gender neutrality, as of mid-2017 there were still at least 25 countries in the world that provided different rights for men and women to transmit nationality to their children. Gender discrimination impacts on minority communities especially because it can undermine social cohesion over time: women who are stateless or who cannot transmit their own nationality to their children may seek husbands and partners who have nationality papers, who are more likely to be members of other communities. Stateless men from among the minority will in turn find it hard to establish a family.

Many nationality laws and policies also fail to provide adequate substantive and procedural guarantees to ensure that vulnerable children can obtain recognition of nationality, especially orphans, children of unknown parents, or those whose parents have no documented citizenship of their own. While the absence of these legal protections can affect members of any social group, in practice it is those from the poorest and most marginalized communities who are most likely to face negative consequences, including those living in remote areas or who face general discrimination from state structures. Even those states that have the basic legal protections may not have in place the administrative mechanisms to ensure that vulnerable children are in fact able to acquire the nationality to which they are entitled under the law. For example, Lebanese nationality law provides that children born in Lebanon who are otherwise stateless shall acquire Lebanese nationality, but in practice children born in Lebanon of stateless parents are not recognized as Lebanese. This affects many people whose ancestors were resident in Lebanon but never registered as Lebanese nationals when the state was first created at the end of the Ottoman Empire, as well as those who were more recently refugees from Palestine.

Children may also be placed at risk of statelessness by lack of birth registration. Although a birth certificate is not usually proof of nationality, it forms proof of the facts that enable the child or future adult to claim or acquire nationality, whether in the state of birth or in another state. Lack of birth registration over multiple generations is one of the most common reasons for statelessness, as proof of connection to a potential state of nationality is lost: as of 2013 the births of nearly 230 million children in the world under age five had never been recorded. Birth registration is often especially difficult to access for the children of refugees, migrants with irregular status and minority groups living in areas unserved by state services or who generally face discrimination in that society.

In many countries, civil status events are only legally recognized if they are registered with the authorities, which can impact on transmission of nationality. In Indonesia, for example, lack of a marriage certificate can prevent registration of a child’s birth, and in turn prevent acquisition of Indonesian nationality. The fact that marriages that take place following traditional indigenous religious practices are not recognized by the state of Indonesia means that children of these marriages are more vulnerable to being undocumented and/or ultimately stateless.

Photo: Fulani people in Sudan. Credit: Rita Willaert.

-

Asia hosts the largest number of people identified by UNHCR as being stateless, including the largest single population of stateless persons in the world, the Rohingya minority of Myanmar, numbering almost one million. However, statelessness is certainly significantly underreported: among several countries with missing statistics, UNHCR records no stateless persons in India or China, the two most populous countries in the world, despite known problems with nationality documentation and statelessness.

The causes of statelessness in the region include problems created by state succession affecting historical migrants among the former territories of the Soviet Union and British Empire. National laws are exclusively descent-based in many countries, generally lacking protections against statelessness, and discrimination on the basis of gender, race and religion are significant problems in South and South East Asia in particular. This creates an environment where minorities may be vulnerable to statelessness. A number of indigenous communities are also not recognized as nationals, despite long-term roots in their country of residence, as are some nomadic and other cross-border communities.

The crisis of statelessness among the Rohingya minority of Myanmar, as well as Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh and across the region, represents not only the largest number of people from one community recorded as stateless anywhere in the world, but also the most severe form of persecution of people rendered stateless by deliberate government action. In 1982, Myanmar changed its law so that nationality was automatically acquired at birth only by members of 135 listed ethnic groups. Rohingya, a Muslim minority in the Buddhist-majority country who mainly live in Rakhine (Arakan) state on the Bangladesh border, were among those excluded by this law; though other minorities, including people of Chinese or Indian origin, were also affected. After communal violence erupted in Rakhine state in early June 2012 the government stepped up its persecution, launching a campaign to forcibly relocate or remove the state’s Muslims; in 2017, violence against Rohingya escalated again, driving hundreds of thousands of new refugees into Bangladesh. Myanmar asserts that its Rohingya population are in fact Bangladeshi – a claim denied by Bangladesh, which does not recognize the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh as nationals.

Communities divided by modern borders from ethnic kin face problems of statelessness in several states, including members of the ethnically Cambodian Khmer Krom community in Vietnam.

A somewhat similar presumption of foreignness applies to the descendants of historical migrants, including migrants who arrived before the country existed. Malaysia, for example, hosts tens of thousands of stateless descendants of Tamil migrant workers brought to the country by the British before independence. Similarly, the children of migrant workers from the Philippines, Indonesia and elsewhere born in Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo are unrecognized as nationals by any state. While the situation of people of Chinese ethnicity in Indonesia has improved through law reform undertaken in 2006, some are still stateless. Sri Lanka has undertaken major efforts to naturalize the descendants of Tamil migrants brought by the British to work on tea plantations, though some may still remain undocumented. Many Urdu speaking Biharis in Bangladesh were stateless, based on their support for Pakistan during the Bangladesh war of independence, though the Supreme Court ruled in 2008 that they should be granted citizenship. There is a community of several hundred stateless people of Chinese ethnicity in Kolkata, India, descendants of a historically much larger population.

In Buddhist-majority Bhutan, too, around 80,000 people are estimated to be stateless, the majority of them Hindus of Nepali origin, the descendants of migrant workers arriving since the 19th century. Like Rohingya, members of this community were in the past recognized as citizens. However, a policy of ‘Bhutanization’ placed that status under threat. In 1977 and 1985, new citizenship acts tightened the qualifications for citizenship, creating a descent-based framework that required both parents to be citizens for a child to acquire citizenship at birth. A 1988 census marked an escalation in measures against Nepali-speakers, in which many were denied recognition of citizenship through the tightened application of these rules. More than 100,000 people fled or were expelled to Nepal and India, where they became stateless refugees; others remain stateless in Bhutan.

Nepal itself has a significant number of people at risk of statelessness in addition to the Nepali-Bhutanese, despite a campaign to increase documentation of nationals. Nepal is one of the 25 countries in the world where the law still retains gender discrimination in transmission of nationality to children: this leaves children of Nepali mothers at risk of statelessness, especially if they marry men from among the Bhutanese refugee community or from the Madhesi minority of Indian origin, who also face discrimination and difficulty in obtaining recognition of either Nepalese or Indian nationality. In Asia, Brunei Darussalam and Malaysia also continue to discriminate against women in their ability to confer nationality on their children. In all these cases, gender discrimination leaves the children of mothers who are from minority groups at greater risk of statelessness – most of all if the child is born out of wedlock. If the father’s nationality is not in doubt, the child does not face that risk: even so, if that nationality is different from that of the mother, or of the country of birth, the child may be forced to accept a nationality that separates him or her from other members of the community.

Indigenous populations following traditional lifestyles in remote areas are also among those most at risk of statelessness. The indigenous people of Thailand’s highland regions, known as the ‘Hill Tribes’, form the majority of the half a million stateless people in Thailand reported by UNHCR. The Thai government has made efforts to increase access to nationality documentation for the stateless people living in these regions. The Orang Asli indigenous community in peninsular Malaysia has many of the same challenges in gaining access to documentation. Malaysia also hosts members of a stateless community also found in the Philippines and Indonesia, the Bajau (or Sama) Laut, or sea gypsies, who suffer from the risk of statelessness that affects nomadic peoples in many regions of the world (or those who are perceived to be nomadic, even if they are now settled). Moken hunter-gatherers found in the coastal regions of Myanmar and Thailand face similar problems.

Forced migrants form another category at risk of statelessness across the Asian region, including Rohingya refugees, as well as Tibetan refugees in India and elsewhere, and Cambodian refugees from the Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s still living in Vietnam who have not yet benefited from UNHCR’s efforts to persuade the Vietnamese government to grant them citizenship. Vietnamese-ethnicity refugees from Cambodia who returned to Cambodia after the fall of the Khmer Rouge also face statelessness. The northeast states of India, between Bangladesh and Burma, house a number of minority groups with origins in neighbouring countries now at risk of statelessness, including members of the Chakma people of Arunachal Pradesh, who fled Bangladesh in the 1960s, and other descendants of Bangladeshi refugees (or people asserted to be so) now living in neighbouring Assam.

Similarly, there are some thousands of Hindu refugees from the partition of Pakistan who live as stateless persons in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir; and an unknown number of stateless people among the Tamil refugees from Sri Lanka still living in southern India. Pakistan also hosts refugees from the Bangladesh war of independence, including Bengalis, Biharis and Burmese who are not considered as nationals by Pakistan, Bangladesh or Myanmar. The decades of conflict in Afghanistan leave an undoubtedly large number of displaced persons at risk of statelessness, both inside and outside the country; among the most vulnerable are members of ethnic groups facing general discrimination, such as the traditionally nomadic heterogeneous set of communities known by the collective label of Jats.

Generally, the low rates of birth registration in South and South East Asia place children at risk of statelessness, especially those facing discrimination of various kinds, including perhaps up to 30 million children in China without official registration, many born in violation of the one-child policy or the children of North Korean refugees. In Indonesia, for example, legal and procedural obstacles mean that children born out of wedlock – or whose parents do not have a marriage certificate – are significantly less likely to have their births registered. This especially affects those who marry under customary or religious rites.

Across the countries of Central Asia, statelessness is largely a consequence of the persistence of ethnic-based discrimination in the aftermath of state succession, affecting minorities in particular. Although the majority of those who were not living in their ‘kin-state’ following the break-up of the Soviet Union have been able to resolve their status, UNHCR still reports stateless populations of several thousand in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and a total of more than 80,000 in Uzbekistan. Most of those affected are former Soviet citizens, of Russian or other Central Asian ethnicity. There is also a population of stateless Kazakhs in Mongolia.

The stateless populations in Asia illustrate global patterns, where the establishment of new boundaries in the aftermath of empire, or the uprooting of people by conflict, creates new minorities and leaves some at risk of statelessness. The creation of adequate systems to provide documentation of citizenship to those displaced, or with ties to several states, has not been a sufficient priority. Racism and other forms of discrimination have contributed to the persistence of statelessness among minorities, in some cases leaving multiple generations with no resolution of their status.

Photo: Ethnic Vietnamese children living on the Tonle Sap lake in Cambodia. Credit: Pippa Hardisty.

-

by Nicole Girard

Rohingya are an ethnic, religious and linguistic minority, traditionally concentrated in the northern part of Myanmar’s western Rakhine state, on the border with Bangladesh. Most practice Sunni Islam and speak the Rohingya language. They are considered the largest single group of stateless people in the world and together are thought to account for as many as one in every seven stateless persons. Described by the UN as the world’s most persecuted minority, their current predicament has been in large part facilitated by their lack of citizenship – the culmination of a long history of violence and discrimination.

Though up to date official statistics on the population of Rohingya do not exist – the government refuses to recognize the term Rohingya and has typically referred to them as ‘Bengali migrants’, excluding them from the last census conducted in 2014 – it did estimate a population it referred to as a ‘non-enumerated population in Rakhine state’ of just under 1.1 million. Many have been forced to flee their country due to continued attacks by security forces, vigilante groups and extremists: the most recent wave of violence, beginning in August 2017, has displaced almost half a million Rohingya into Bangladesh.

Even before then, however, hundreds of thousands were living outside the country, predominantly in Bangladesh but also Malaysia, Thailand and further afield. The vast majority of Rohingya are regarded as stateless and most outside Myanmar are also refugees – a direct result of having been denied citizenship by the Myanmar government.

A long history of persecution

The history of Rohingya is contested by Myanmar authorities as part of their sustained campaign to repress their claims to citizenship: the government asserts that they are descendants of immigrants from India and Bangladesh, encouraged by the colonial administration. Evidence to the contrary is compelling, however: one often cited record is that of Scottish doctor Francis Buchanan, writing in 1799, who documented that Arakan was also known as ‘Rovingaw’ among ‘Mohammedans [Muslims], who have been long settled in Arakan, and who call themselves Rooinga, or natives of Arakan’, almost a quarter-century before the colonial era. Indeed, many scholars trace the first Muslim communities back to the early 15th century.

Relations between Rohingya and other Burmese communities had already deteriorated during the Second World War, when tensions rose as the conflict between the British and the Japanese polarized loyalties, with Rohingya siding with the former. Nevertheless, after Myanmar’s independence from Britain in 1948, the parliamentary government recognized Rohingya as citizens and referred to them as Rohingya, even Prime Minister U Nu, and issued government identification. Furthermore, an area in what was then Arakan state was administered separately to the rest of majority Buddhist Rakhine.

Nevertheless, Rohingya were increasingly estranged as Burmese authorities purged the military and civil administration of Muslims, in the process detaining many Rohingya leaders arbitrarily. In the ensuing years, a low-level secessionist movement brewed in northern Arakan. Following the coup under Nu Win in 1962, a sustained military presence was imposed on the area, with frequent military interventions that made little effort to distinguish between rebels and civilians. This was accompanied by a broader erosion of the civil and political rights of the Rohingya people, reinforced by increasing rhetoric of Rohingya as ‘illegal immigrants’. By 1970, Rohingya were no longer being issued national registration cards and in 1974 they were denied the right to move – a significant turning point in their reclassification from citizens to stateless ‘immigrants’.

The road to statelessness

The 1982 Citizenship law served to finally disenfranchise Rohingya of their citizenship rights. It created three classes of citizens: full, associate and naturalized citizens. Full citizens are those that belong to one of the listed 135 ‘national races’ or those who can prove that their ancestors were in the country prior to the start of British colonization in 1823 or by descent; associate citizens are those who qualify for citizenship under the previous citizenship law of 1948, but who cannot prove that their ancestors were in the country prior to 1823, so do not qualify under the 1982 law; and naturalized citizens are those that can prove their parents entered the country before 1948,. The three classes of citizens do not enjoy equal rights under the law.

The law is thought to have been designed specifically to undermine the rights of Rohingya. Since they are not included in the ‘national races,’ Rohingya must trace their lineage back almost two centuries to prove their continued inhabitation in the country. But because of systematic disenfranchisement, many Rohingya have difficulty proving legal residency as they have routinely had their documents confiscated and are arbitrarily deprived of their citizenship.

A citizenship verification drive began in 1989, whereby people were issued colour-coded identification cards based on the class of citizenship. Applicants were asked to submit their old national registration cards, but for many of the Rohingya who returned from Bangladesh following the mass displacements in 1991, they did not receive replacements but were instead issued white ‘temporary registration cards’, regardless of any outstanding claims to citizenship or supporting documentation.

The white card did, however, enable Rohingya to vote in the 2010 general and the 2012 bi-election. These white cards were subsequently revoked in early 2015, barring card holders from voting or standing for parliament in the 2015 elections. This also had the effect of dispossessing approximately 700,000-800,000 people, most of whom were Rohingya, of their only form of legal status identification.

The transition to civilian government has only further eroded the rights of Rohingya. More rounds of citizenship verification were initiated, starting with Thein Sein from 2012-2015 and continuing with Aung San Suu Kyi in 2016. Both have largely failed due to restrictions on self-identifying as Rohingya, distrust from affected populations, unclear processes and opposition from anti-Rohingya Buddhist nationalist groups.

The denial of citizenship has been used to justify further exclusion, marginalization and institutionalized discrimination. Rohingya have been subject to travel restrictions for decades but restrictions on travel increased after the violence of 2012. Such violations on the freedom of movement greatly limits rights to healthcare, education, livelihood opportunities and religious activities. Even free travel between or within townships is not permitted and requires a lengthy and expensive approval process by the local administration, violation of which is a punishable criminal act.

Other restrictions were tightened in 2012, including those on birth, death, immigration, migration, marriage, construction of new religious buildings, land ownership and the right to repair and construct buildings. Violating these restrictions result in harassment, extortion, detention and abuse by authorities. Their lack of citizenship bars them from being employed by the government, including as doctors, nurses and teachers.

Restrictions on births and marriage are severe. Rohingya must register births with the local authorities for a fee, but are often denied birth registration for various discriminatory reasons, such as the categorization of many marriages as ‘unauthorized’, as Rohingya must also seek permission from authorities to marry; the Rohingya two-child policy, in place since 2005; or, more frequently, expensive and cumbersome processes. These policies have resulted in around 5,000 unregistered Rohingya babies, also known as ‘black-list babies’, that cannot obtain travel registration, access health and education. Birth registration of Muslim babies in Rakhine reportedly stopped after 2012, leading experts to estimate that half of all babies in Rakhine state do not have birth registration, perpetuating cycles of statelessness.

The situation today

The persecution of Rohingya has entered a deadly new phase over the last year, beginning in October 2016 when in response to attacks on military border posts the army launched major offensives in Rakhine targeting Rohingya indiscriminately and resulting in widespread displacement, death and other human rights abuses. In March 2017, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution to send an international fact-finding mission to Myanmar. The resolution called on Myanmar to eliminate statelessness and institutionalized discrimination, with particular reference to reviewing the 1982 Citizenship law.

More recently, however, violence against the community has escalated following an attack by a recently formed Rohingya armed group on Burmese security forces in August 2017 that enabled the military to initiate a devastating ‘clearance operation’ that has targeted unarmed Rohingya men, women and children indiscriminately. Amidst reports of brutal atrocities, village burnings and the rape, torture and murder of hundreds of Rohingya, a wave of mass displacement has pushed close to half a million Rohingya to cross into Bangladesh, with more crossing the border daily as the ethnic cleansing of Rakhine by Burmese forces continues.

In this context, the focus in much international coverage has understandably been on the immediate impacts of this violence and the need to provide urgent humanitarian support. Yet to ensure a long term and peaceful end to the brutal persecution of Myanmar’s Rohingya, their full citizenship must also be urgently restored. Their state’s representation of Rohingya as illegal migrants or ‘Bengalis’ belonging in neighbouring Bangladesh, reflected in their stripping of their nationality and associated rights, has played an important role in enabling human rights violations against the community. Ending the impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators of these abuses requires, firstly, that they are recognized as citizens of Myanmar – a step that the government, including State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, has so far refused to contemplate.

At the same time, the long term stigmatization of Rohingya is so deep-rooted in society that meaningful inclusion will require far more than administrative or legal reform, important though that is in providing a measure of security to the community. These processes will also need to be accompanied by community resolution and education at a social level to ensure entrenched prejudice towards the community is steadily eroded. Myanmar’s system of institutionalized racism and discrimination effectively ensures the Rohingya population remain in a condition of statelessness: for this to be resolved effectively, then, requires a comprehensive end to its protracted exclusion of its Muslims citizens, reform of the citizenship law and a broader programme of social, political and economic emancipation.

Photo: Rohinyga in Myanmar. Credit: Mathias Eick EU/ECHO.

-

by Nicole Girard

International media attention on indigenous sea nomadic populations increased dramatically after the Indian Ocean tsunami that struck the coast of Thailand in 2004. Most examined traditional knowledge of the ‘sea gypsies’ that enabled them to take shelter on inland hills and warn others of the impending danger, soaked with romantic depictions of lives dominated by the sun and sea. Very little, however, focused on their extreme marginalization as communities denied the right to nationality by both the Thailand and Myanmar governments.

The group in question were Moken, an indigenous seafaring people whose ancestral territories are found in the 800 islands of the Mergui Archipelago, off Myanmar’s southern coast, continuing into Thailand’s Andaman Islands off Ranong and Phang Nga provinces. Their marine nomadic lifestyles have similarities with others in Southeast Asia, including the Orang Laut of the western Thai-Malay peninsula to the Riau Archipelago and the Sama-Bajau of Sabah, Malaysia, eastern Indonesia and the southern Philippines. These are generally broad classifications, however, belying much ethnic and linguistic diversity.

Sea nomadic groups have been adept at avoiding the influences of the state, travelling across maritime boundaries and refusing to be held to any one nation’s laws. Historically, living on the sea was a tactic to avoid conflict, disease, taxation and other limitations that came from mainland settlement. That is not to say they that they did not have significant ties with land-based groups, as trade in marine resources has been a cornerstone of these interactions for centuries.

But the mainland world has now caught up with them. Over the past few decades, as borders became more established, with governments focused more on maritime security and environmental conservation, the lifestyles of seafaring indigenous groups became more restricted. Some groups were targeted for terrestrial sedentarization programmes as early as the 1950s, an approach frequently replicated on other sea nomadic populations in the ensuing decades. Many of those who have settled and integrated have been accepted as nationals of their respective states. Others have found no easy path to citizenship.

Moken of Thailand and Myanmar

Moken are one of Thailand’s three traditionally sea nomadic populations, along with Moklen and the Urak Lawoi. While their origins are disputed, a recent study of Moken mitochondrial DNA suggest that the Moken originated in coastal mainland Southeast Asia, moving into the island areas several thousand years ago.

According to the Chumchon Thai Foundation, an NGO working with Moken, there are 2,100 Moken in Thailand In Myanmar, estimates suggest there are at least 3,000 living on islands of the Mergui Archipelago. It is unknown exactly how many Moken are stateless, but they remain more vulnerable to statelessness than Thailand’s Moklen or Urak Lawoi, who have maintained a more land-based existence and have integrated more firmly with the Thai state.

Amendments to the Thai Nationality law in 2008 removed some restrictions that were preventing Moken and other indigenous peoples from being eligible for citizenship. Still, applicants must provide proof of birth and domicile in Thailand, either through a birth certificate or, where that is not available, witness testimony, hospital records or a DNA test establishing connection with a Thai citizen. Such documentary evidence is very difficult to provide, as many Moken either did not have their births registered or registration was refused by some local hospitals and civil servants.

Without citizenship or Thai government identification, Moken are vulnerable to a host of rights violations. They typically struggle to access the low cost subsidized healthcare system, for example: many go without treatment unless the situation is dire, and then they are hit with large medical bills that they cannot afford. While all children irrespective of their citizenship or lack of citizenship have the right to attend public schools in Thailand, many face discrimination based on their ethnicity or lack the basic supplies to attend, while others drop out early to help their parents earn a livelihood.

Their insecure legal status makes them prey to middle men that coerce Moken into low paid, dangerous or illegal employment, particularly those that exploit their ability to stay underwater for long periods. These include diving for rarities such as sea cucumbers and abalone, or working on fishing boats that use dynamite to catch fish, staying under water with the support of surface air supplied through tubes using diesel-run compressors. Because of this unsafe diving technique and pushing to unsafe depths, it is common for Moken men to suffer from decompression sickness, leading to death or disablement while others have died or lost limbs from the exploding dynamite. They are not compensated for their injuries or inability to work.

While there is no figure available on the number of Moken at risk of statelessness, one case study from 2012 reported that the islands of Koh Lao, Koh Chang and Koh Phayam had 600 Moken people that were not yet determined eligible for citizenship, but instead had been given the ‘zero card’. Approved for issuance to the Moken in 2010, the card does not allow them free movement outside their district, access to health services, social security or labour protection.

Moken are known as Salon or Selung in Myanmar, where they are considered one of the 135 ‘national races’ that are automatically eligible for citizenship. Despite this, many have not been able to acquire Myanmar nationality. In the 1990s, faced with forced relocation and settlement, many fled to the seas. Their remoteness and movement across borders have prevented access to civil documentation to confirm their nationality, while human rights groups have documented reports of abuse, intimidation and violence by Burmese authorities, including being shot at and killed by the Burmese navy.

Sama Dilaut

Often referred to as Bajau Laut, Sama Dilaut are the diverse semi-nomadic and often migratory groups that have traditionally roamed the islands of the Sulu-Sulawesi Sea located between the southern Philippines, the coast of Sabah, eastern Malaysia, and Sulawesi and east Kalimantan, Indonesia. Their range reaches as far as the Arafura Sea off the coast of Papua, Indonesia, as well as north to the South China Sea. There are settled populations of Sama Dilaut throughout the region, mostly in Indonesia and the Philippines, but also some in Sabah, Malaysia, as well as a small population of mobile family groups, but – like the Moken and others – there are no clear estimates of their numbers.

In Semporna, a district on the eastern coast of Sabah, a significant population of Sama Dilaut reside. The Eastern Sabah Security Command began conducting an official census of the Sama Dilaut in 2016, but their findings have not yet been released. They estimated that there were approximately 1,800 families in Semporna. Other data complied from the Semporna District Office and the Sabah Parks authority further suggested that the community amounted to a total of 8,344 people, of whom around 45 per cent (3,776) were believed to lack citizenship. In another study, 40 per cent of the population residing in Tun Sakaran Marine Park, off the coast of Sempora, were Baja Laut. While these data were not disaggregated for Sama Dilaut ethnicity, of the total population of the park, only 17 per cent were Malaysian citizens, 43 per cent had some sort of official or unofficial documentation, and the remaining 4o per cent had no documentation, placing them at a high risk of statelessness.

Historically, Sama Dilaut have maintained a nomadic lifestyle in the waters between Philippines and Sabah, with some Sama Dilaut choosing to settle on coastal areas in recent years. Clashes on the island of Mindanao and the islands of the Sulu archipelago between the government of the Philippines and the Moro National Liberation Front in the 1970s led many Sama Dilaut to flee the area to the safer waters of Semporna, joining a pre-existing population of Sama Dilaut. Many were provided with an IMM13 residency permit which was renewable yearly for a fee. Although it allows holders to live and work in Sabah, it limits travel and does not allow access to public education or subsidized healthcare. Children of IMM13 holders were entitled to apply for IMM13 based on the status of their parents although many card holders were not aware and did not obtain any documentation for their children; others were unaware of the requirement to renew their cards.

The Malaysian Federal Constitution however does have safeguards against statelessness. It states that any child born in Malaysia who is not born the citizen of another country, and cannot acquire citizenship from another country within one year of birth, can be a citizen. Yet this provision has not been successfully implemented in practice, given the lack of procedural guidance for applicants relying on this provision. The Malaysian courts recently reviewed this provision and imposed a heavy evidential requirement on applicants to prove that they are not a citizen of any other country. The issue is further complicated in Sabah, as it maintains autonomy from the federal government over immigration matters.

Similar to the situation of the Moken, without citizenship the Sama Dilaut are marginalized, excluded and denied their rights. Unlike Thailand though, their children are not permitted to attend public schools in Sabah, nor can they access subsidized health care, leaving their children exposed to preventable diseases like diarrhea and pneumonia. They are also vulnerable to forced evictions and arbitrary detention.

In 2013, the situation was exacerbated when over two hundred armed militants, the followers of a claimant to the Sulu sultanship, invaded eastern Sabah in the attempt to ‘reclaim’ the area. After a month-long showdown with Malaysian security, the area was designated as the Eastern Sabah Security Zone (ESSZone). Sama Dilaut were targeted for security crackdowns, imprisoned and deported to the Philippines, maligned as illegal criminals in national media. As a result, many Sama Dilaut fled to other areas, only to be caught in Indonesian waters for illegal fishing. In 2014, over five hundred Sama Dilaut were detained in east Kalimantan, the majority of whom did not have identification.

An uncertain future

The broader discrimination faced by indigenous seafarers is manifested in its most extreme form through statelessness and a lack of a nationality documentation, leaving them on the margins, with no hope of their situation ever being resolved. Nomadic sea populations are among the most at risk, as they are forced to abandon their traditional lifestyle to fit in with the demands of the modern nation state. Without safeguards for their rights, their distinct cultures and lifeways are directly under threat. A balance must be struck between gaining the benefits of lives as citizens, but also having their rights as indigenous peoples protected as well.

Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines all have some level of indigenous rights protection. Very rarely has this protection been effectively extended to nomadic seafarers, however, as these rights frameworks are applied to land-based groups and become more complex in the realm of traditional marine territories. Their role in the protection and conservation of marine areas has been largely denied, tied to their precarious legal status, compounded by discrimination by the wider society. Indonesia in particular protects the rights to traditional fishing, but these rights are only applicable to Indonesian citizens.

In the meantime, despite the attention they have generated in recent years, indigenous seafarers are still invisible, increasingly pushed out of their old traditions while unable to integrate as citizens on land. Until their situation is properly acknowledged and resolved, the chance of a better future for themselves and their children remains only a distant possibility.

Photo: Indigenous sea nomads off the coast of Semporna, Malaysia. Credit: Imran Kadir.

-

Sama Dilaut, also known as Bajau Laut, are an ethnic group of Malay origin who traditionally live a nomadic lifestyle at sea. They are known to be affected by statelessness (read more in the previous chapter). In the last few decades many have been forced to settle permanently on land, but a dwindling number still call the ocean home, living on long boats known as lepa lepa. Traditionally, they fish with nets and lines and are expert free divers, going to improbable depths in search of pearls and sea cucumbers or to hunt with handmade spear guns. This photo story by James Morgan depicts their way of life at sea, shot off the coast of North Sulawesi, Indonesia.

A collection of traditional, handmade Bajau lepa lepa boats off the coast of Pulau Bangko. More and more Bajau are abandoning their traditional nomadic lifestyle to settle in permanent homes in stilt villages, but a dwindling few still choose to live the majority of their lives at sea. Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Whilst few young Bajau are now born on boats, the ocean is still very much their playground. And whilst they are getting conflicted messages from their communities, who simultaneously refrain from spitting in the ocean and continue to dynamite its reefs, I still believe they could play a crucial role in the development of western marine conservation practices. Here Enal plays with his pet shark. Wangi Wangi, Indonesia.

In addition to the nets and lines traditionally used for fishing, the Bajau use a handmade ‘pana’ for spearing their catch. Pulau Papan, Togian Islands.

Moen Lanke wrenching clams from the reef with a tyre iron. He holds his breath for long minutes underwater while the work is done. Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Jatmin, an octopus specialist, carries his freshly speared catch back to his boat in the shallow waters off the coast of Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Despite the majority of Bajau now living in stilt communities and adopting cosmologies more in line with land-based communities, they still build their mosques over the ocean and practice a syncretic belief system that allows for a deep reverence for the ocean and the spirits that are said to inhabit it. Torosiaje, Indonesia.

Ibu Diana Botutihe is one of the few remaining Bajau, indeed one of the few remaining people in the world, to have lived her entire life at sea, visiting land only intermittently and as a matter of necessity in order to trade fish for rice, water and other staples. -

The countries of North, Central, and South America for the most part share a common tradition of attribution of citizenship based on birth in the territory, known as the jus soli rule. Notwithstanding some caveats, this rule broadly provides protection against statelessness and means that the continent as a whole has the lowest number of stateless people compared to other regions of the world. Therefore, in most of these countries, it is likely that the majority of those who are stateless are migrants – that is, those affected have themselves moved from another country.

However, some countries have used restrictions to the jus soli rule to exclude significant numbers from citizenship, including the descendants of migrants over several generations, while lack of birth registration leaves the status of others in doubt. Mapping of statelessness in the continent is limited, but national studies have begun to highlight the previously hidden situation of stateless individuals: a 2012 study of statelessness in the US, for example, highlighted the plight of stateless asylum seekers and migrants, many of them held in immigration detention. They may face particular challenges both as members of ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities in their country of origin and within the US and also as stateless individuals. Research in Canada has shown a similar picture. For the region as a whole, UNHCR reported a total of 136,585 stateless persons in the Americas as of 2015, almost all of them (133,770) in the Dominican Republic. In its 2016 Global Trends report, however, the figure for the Dominican Republic was left blank to reflect efforts underway to resolve this situation – though the problem of statelessness in the country is far from being resolved.

Indeed, the ongoing statelessness crisis in the Dominican Republic remains the most important in the region. The situation primarily affects the descendants of Haitian migrant workers in the sugarcane industry, and is at least partly based on racism against people of African descent. Under the 1929 Constitution, children born in the country were automatically attributed Dominican nationality, unless their parents were diplomats or ‘in transit’, a condition historically interpreted as meaning present in the country for only a few days. From the early 1990s, however, the Dominican government implemented a series of administrative, legislative and judicial measures aimed at restricting access to Dominican nationality.

In 2004, a new migration law formally designated temporary foreign workers and undocumented migrant workers as foreigners ‘in transit’, followed in January 2010 by a new Constitution which provided that children born in the Dominican Republic whose parents were irregular migrants no longer had the automatic right to Dominican nationality. In 2013, the Constitutional Court gave an extraordinary judgment that ruled that children born in the Dominican Republic to foreign parents who did not have regular migration status had never been entitled to Dominican nationality – a judgment applied retrospectively to people born since 1929. Although a new law was adopted under international pressure in May 2014 to restore access to nationality for some, it did not automatically benefit those born before the 2010 Constitution came into effect, though it provided some limited rights for them to apply to (re-)acquire Dominican nationality. Tens of thousands of people remained stateless, some of whom had been deported to Haiti but were not recognized there as nationals.

The government’s crackdown on the Dominico-Haitian population can only be fully understood in the broader context of their extreme discrimination as a minority within the country, a long history of exploitation and persecution that included periodic attacks against them, including the notorious 1937 ‘Parsley massacre’ where thousands of ethnic Haitians were murdered by Dominican soldiers.

People of Haitian descent are also at risk of statelessness in the Bahamas, where perhaps up to one quarter of the population are of Haitian origin. Though many are citizens, some have faced difficulties in asserting rights in the Bahamas although they have lost any connection to Haiti. Unlike most other countries in the Americas, the Bahamas generally attributes citizenship on the basis of descent, while gender discrimination persists in nationality law, creating additional barriers to citizenship.

Other countries in the region ensure that the children of migrants are able to access nationality, providing a contrast to the Dominican Republic. In Chile, for example, after some years of political controversy in the interpretation of the meaning of a parent being ‘in transit’, the Civil Registry stated in 2014, in line with a series of decisions by the Supreme Court, that it would record the Chilean nationality of children born in the country, with exceptions only for children of short-term visitors. Those most impacted by previous restrictions were the children of low-income migrants, especially those of African descent.

Another group at risk of statelessness in the Americas are members of indigenous populations living in border regions. In countries with a legal framework providing citizenship on the basis of birth in the country, birth registration is especially important for proof of citizenship, since it is the only legally accepted proof of location of birth. Those living in remote areas are least likely to access civil registration, and some may even actively avoid contact with state services. Problems related to statelessness among indigenous peoples resulting from lack of birth registration are not well studied, but have been reported in a number of Latin American countries, including Brazil, Chile, and Columbia. Among these groups are Aymara living on the border of Chile and Peru, as well as Wayuu residing in a zone extending across the national borders of Colombia and Venezuela. Children of undocumented migrants or displaced people, or generally those from poor families, are also more likely not to have their births registered, leaving them at risk of various forms of exclusion, including statelessness.

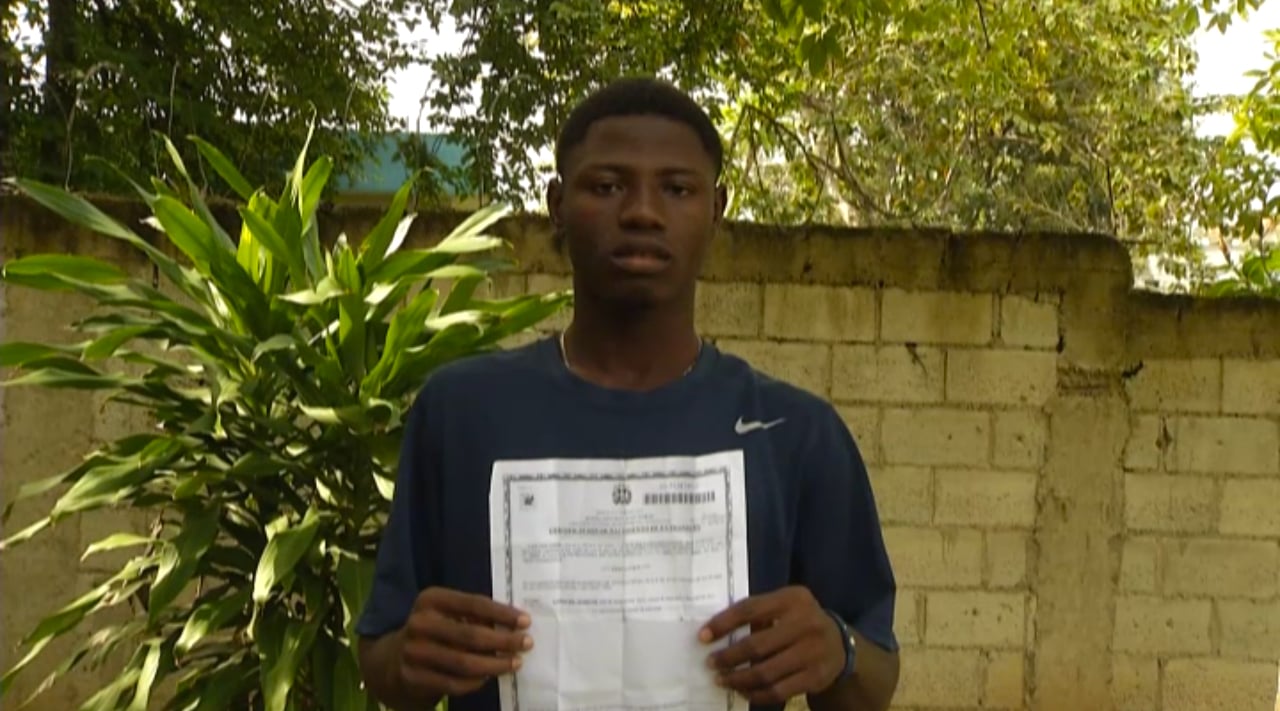

Photo: Dominican man of Haitian Descent – still taken from MRG’s film ‘Our Lives in Transit’.

-

‘Our Lives in Transit’ is a 30-minute documentary showing life in the Dominican Republic in the aftermath of a controversial law that leaves over 200,000 people doubting their own identity.

Rosa Iris is a young and determined lawyer; we experience a year in her life as she fights for the rights of her community.

There is a huge threat over her and others in her position. She is no longer allowed to call the country she was born in, home. ID documents are being confiscated, buses are picking up anyone without proof of who they are and deportations have started.

Despite living in the Dominican Republic all their lives, Dominicans of Haitian Descent face daily discrimination, sometimes violent. Because their parents or grandparents were born in next door Haiti, but mainly because they are black.

This story of migration and nationality, rejection and belonging resonates with people all over the world. Identity and integration have never been so relevant, as we face a global crisis over who has the right to live where, how communities form and who we are.

-

Europe has both the most information about stateless populations and the most developed set of standards relating to nationality and discrimination. Nonetheless, statelessness is still prevalent across the region. As of the end of 2016, UNHCR estimated that close to 600,000 people were stateless in the European region, a figure made up primarily of linguistic minorities in a number of post-Soviet states, Roma, and more recent refugees, asylum seekers and migrants primarily from outside Europe.

A significant number of stateless minorities were created in the aftermath of the break-up of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Europe’s largest stateless population is in Latvia, recording more than 240,000 people, largely Russian-speakers, who after Latvia’s independence found themselves classified as ‘non-citizens’: while they enjoy most of the same rights as other Latvians, they cannot vote or work in the civil service. There is also a large number of stateless Russian-speakers in Estonia (more than 85,000) and a much smaller number in Lithuania. Ukraine similarly hosts some 35,000 stateless people, mainly former Soviet citizens, who have significantly fewer rights than those in the Baltic states.

In the Russian Federation, the 90,000 people still identified as stateless by UNHCR mostly migrated from other parts of the Soviet Union and failed to acquire citizenship during the post-Soviet period; following a change of law in 2002, they were considered to fall in the same category as any other foreigner, and for one reason or another they have not benefited from various efforts to facilitate naturalization. Among this total are people of many different ethnic groups, but especially those who are of low status, such as Roma; or who were the subject of forced relocations during the Soviet era, including Meshketian Turks, originally from the border zone with Türkiye in southwest Georgia. Existing patterns of discrimination towards minorities are therefore replicated to some extent among the stateless population.

Stateless Roma are spread across a number of European states, especially in Russia, Slovakia and the countries of the former Yugoslavia; some who fled as refugees from Yugoslavia remain stateless in other parts of Europe, such as the significant numbers of stateless Roma in Italy. Many thousands have no administrative existence at all, lacking birth registration or any other official recognition from the State. They thus live entirely outside of any form of basic social protection or inclusion. The plight of stateless Roma thus creates an extreme version of the general discrimination faced by the Roma community in many European states, including difficulties with access to housing, schooling and health care.

The other sizeable population of stateless persons in Europe results from migration, largely from outside the region. Some of these people who arrive in Europe were already stateless minorities in their country of origin: for example, there are many stateless Kurds among the Syrian refugee flows, but often not identified as stateless as well as refugees. Others have become stateless as a result of their journeys: while the legal situation has not changed as a result of their flight, their documents have been lost or destroyed during the journey, and they are unable to provide sufficient evidence to persuade the consular authorities of a country of origin of their nationality. These people are now becoming significant minorities in their own right in European countries: for example, in Sweden, the figures reported by UNHCR for stateless persons in the country climbed from 20,450 at the end of 2013 to 36,036 at the end of 2016, mostly among refugees. In light of this total, the 198 stateless people reported in Greece at the end of 2016 is not a plausible figure.

As elsewhere, stateless migrants and asylum seekers can find themselves in a limbo due to lack of recognition in their host country. Where European countries provide access to naturalization, these stateless people will mostly be able to acquire nationality in their host countries. However, those who are not refugees and who arrive in countries that do not have statelessness determination procedures may remain without any legal status. At the same time the state cannot deport them because no other state will recognize them as its nationals. As millions of refugees have already entered Europe and more continue to come, fleeing conflicts and persecution elsewhere, ensuring an inclusive and open citizenship regime will be essential to avoid creating sizeable stateless minorities. Although the majority of European states have some safeguards in place to confer nationality on otherwise stateless children born on their territory, many of these safeguards are incomplete and do not meet the standards set by international law.

Photo: Children at a Roma settlement in Slovakia. Credit: Blue Delliquanti.

-

by Julija Sardelić